The Enfield Haunting – A Deep Dive into Britain’s Most Documented Poltergeist Case

It’s late August 1977, and the stillness of a quiet council house at 284 Green Street, Enfield, North London, shatters under a sudden, inexplicable uproar. Inside, furniture shifts without a hand to guide it—chairs sliding, beds trembling—while a cacophony of knocks echoes from the walls. For Peggy Hodgson and her four children, this is no fleeting anomaly but the beginning of a descent into chaos, their lives unraveling thread by thread under the weight of forces they cannot see or explain. What started as a restless night would soon spiral into one of the most documented and contentious paranormal cases ever recorded.

The Enfield Haunting, spanning from 1977 to 1979, stands as a towering enigma in modern British history—a saga of alleged poltergeist activity that gripped the Hodgson family and drew in investigators, journalists, and skeptics alike. At its heart are Peggy’s daughters, Janet and Margaret, whose claims of levitating beds, flying objects, and a disembodied voice would ignite a firestorm of belief and disbelief. For some, it remains a rare window into the supernatural; for others, a cautionary tale of human frailty and fabrication. Nearly half a century later, the case endures as a lightning rod, its echoes felt in everything from hushed debates to Hollywood screens.

In this investigation, we’ll sift through the layers of the Enfield Haunting—firsthand accounts from those who lived it, findings from the investigators who staked their reputations on it, and the sharp critiques of skeptics who saw trickery where others saw mystery. This isn’t about proving or debunking the supernatural; it’s about dissecting the evidence with a steady hand, peering into the cracks where facts blur into questions that refuse to settle. What happened at 284 Green Street? And why does it still hold us in its grasp?

The case’s shadow stretches far beyond its time—its tendrils weaving into pop culture through works like The Conjuring 2 and the Sky series The Enfield Haunting, each retelling amplifying its legend. More than a ghost story, Enfield has become a benchmark for poltergeist investigations—a case so steeped in detail, so fiercely debated, that it challenges us to confront the boundaries of what we’re willing to accept as real. Here, we step into that unsettled ground, tracing the threads of a haunting that refuses to fade.

The Hodgson Family and the First Disturbances

In the summer of 1977, the Hodgson family lived an unremarkable life at 284 Green Street, a modest council house in Enfield, North London. Peggy Hodgson, a single mother in her mid-30s, raised four children on her own: Margaret, 13, a quiet teenager; Janet, 11, an energetic and sharp-witted girl; Johnny, 10, often overshadowed by his sisters; and Billy, 7, the youngest, with a slight speech impediment. Their home, a narrow, three-bedroom terrace in a working-class neighborhood, offered little in the way of luxury—its peeling wallpaper and worn furniture a testament to their strained circumstances. They were an ordinary family, their days shaped by school routines and the hum of a tight-knit community, until the night everything changed.

It began on August 30, 1977, a Tuesday thick with the late-summer heat. Peggy was downstairs when Margaret and Janet, sharing a bedroom, called out in alarm. They claimed their furniture—a heavy chest of drawers—had shifted on its own, scraping across the floor without a push. Then came the knocks: sharp, deliberate raps reverberating from the walls, too loud to dismiss as pipes or neighbors. Peggy rushed upstairs, expecting a prank or a simple explanation, but the room was still—no one near the furniture, no sign of tampering. The knocking persisted, erratic and insistent, as if something demanded attention.

Skeptical by nature, Peggy searched for a rational cause. She checked for intruders, rattled floorboards for loose nails, and even pressed her ear to the walls, hunting for a mundane source. Finding none, her unease grew as the children’s fear mirrored her own. With the disturbances showing no sign of stopping, she made a call that would pull the family into uncharted territory: she dialed the police. Around 1 a.m., WPC Carolyn Heeps arrived, joined by a male colleague, expecting perhaps a domestic spat or a break-in. What they encountered defied their training. Heeps later reported watching a chair slide four feet across the linoleum floor—unassisted, untouched—before it stopped abruptly. No strings, no tricks, just movement she couldn’t explain. Her signed statement, filed with the Metropolitan Police, became one of the earliest anchors of credibility for the Hodgson’s claims, a rare instance of official witness to the inexplicable.

The next few days brought no reprieve. What started with a shifting dresser and rogue knocks escalated into a barrage of chaos. Marbles and Lego bricks—scattered toys of a cluttered home—began flying through the air, striking walls with force. Furniture toppled without warning, heavy wardrobes and tables crashing in empty rooms. The knocking grew louder, a relentless drumbeat that neighbors could hear through the thin walls. For Peggy, a woman accustomed to managing life’s hardships alone, the situation slipped beyond her grasp. The children, sleepless and shaken, clung to her as the house turned against them. Desperate for answers, she reached out beyond Green Street—first to the press, then to those who claimed expertise in the unseen—setting the stage for an investigation that would define their lives.

Enter the Investigators – The SPR and Beyond

As the disturbances at 284 Green Street spiraled beyond Peggy Hodgson’s control, the family’s plea for help found its way to the press. In early September 1977, Peggy contacted the Daily Mirror, a tabloid known for its appetite for the unusual. Reporter Douglas Bence and photographer Graham Morris arrived soon after, stepping into a house thick with tension. Morris, tasked with documenting the scene, quickly became part of it—struck in the forehead by a Lego brick that shot across the room with no visible source. His photographs captured chairs tipped over and toys scattered mid-flight, images that splashed across the paper’s pages and ignited public fascination. The Mirror’s coverage turned a private ordeal into a national curiosity, drawing eyes—and soon, experts—to Enfield.

Word of the case reached the Society for Psychical Research (SPR), a British organization dedicated to studying the paranormal with a mix of rigor and openness. By mid-September, two of its members arrived to take charge: Maurice Grosse, an inventor turned investigator, and Guy Lyon Playfair, a writer with a deep interest in poltergeists. Grosse, in his late 50s, brought a methodical mind and a personal stake—his daughter, also named Janet, had died in a motorcycle accident in 1976, leaving him haunted by grief and attuned to the Hodgson girls’ plight. His emotional connection fueled a relentless drive to uncover the truth. Playfair, younger and more reserved, approached the case with a skeptic’s caution, tempered by years studying similar phenomena in Brazil and a commitment to record what he saw, not what he assumed.

Their investigation was exhaustive, spanning months and eventually logging over 2,000 alleged incidents. Grosse and Playfair set up camp in the Hodgson home, armed with tape recorders, cameras, and notebooks. They recorded hours of audio—capturing knocks, crashes, and later, voices—while photographing anything that moved or defied explanation. They interviewed the family, neighbors, and passersby, cross-referencing accounts to build a timeline of events. Their presence was near-constant, a vigil meant to catch the unseen in action or expose a hoax if one existed. The duo’s collaboration blended Grosse’s fervor with Playfair’s restraint, creating a record that would anchor the case’s legacy, whether as evidence or enigma.

Others came too, drawn by the growing buzz. In 1978, American demonologists Ed and Lorraine Warren made a brief visit, their reputation preceding them from high-profile cases like Amityville. They labeled the Enfield activity demonic—a dramatic flourish that fit their style—but spent little time on-site, their role exaggerated later in The Conjuring 2’s Hollywood retelling. Additional SPR members and curious researchers filtered through, but Grosse and Playfair remained the constants, their work the backbone of the investigation. Together, they transformed a chaotic flurry of claims into a documented phenomenon, one that would demand scrutiny from believers and doubters alike.

The Phenomena – What Was Reported?

At the heart of the Enfield Haunting lies a catalog of events so varied and persistent that they defy easy dismissal—or simple explanation. From August 1977 to 1979, the Hodgson home became a stage for phenomena that ranged from the mundane to the astonishing, each incident meticulously logged by investigators and debated ever since. What unfolded over those 18 months wasn’t a single, tidy narrative but a cascade of disturbances—some witnessed by dozens, others shrouded in doubt—that built the case into a cornerstone of paranormal lore.

The activity began with objects on the move. Furniture slid across floors unassisted—chairs skidding, wardrobes shifting—often in full view of the family or visitors. Books toppled from shelves, pages fluttering as if caught in a gust, while smaller items like marbles and Lego bricks launched with startling force, pinging off walls or striking unsuspecting onlookers. Photographer Graham Morris felt the sting of one such projectile early on, a moment that cemented his belief in something beyond trickery. These movements weren’t sporadic; they recurred with a rhythm that suggested intent, a pattern that investigators scrambled to document.

Then there were the sounds—knocks and raps that punctuated the air like a coded message. They hammered walls and floors, sometimes in bursts, other times in deliberate sequences, loud enough to draw neighbors to their windows. Multiple witnesses, from police to passersby, reported hearing them, their consistency lending an eerie weight to the claims. The noises weren’t static; they shifted locations—upstairs one moment, downstairs the next—eluding efforts to pin them to a creaky joist or a prankster’s fist.

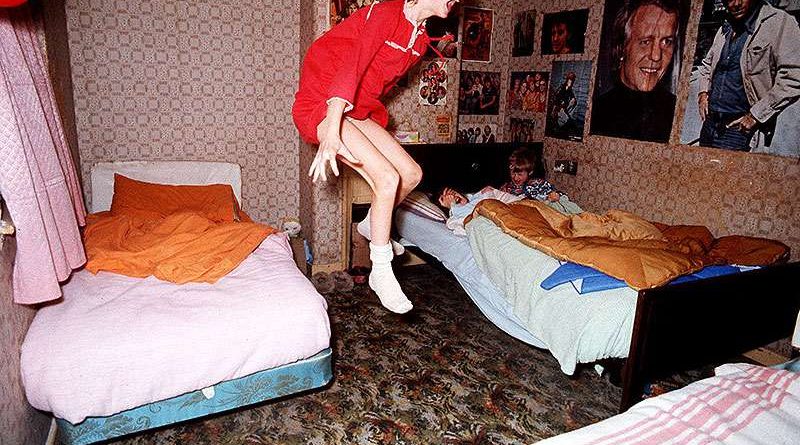

The most striking—and polarizing—claims centered on Janet Hodgson. Reports emerged of the 11-year-old levitating, her body rising from her bed or being flung across the room, events allegedly caught in a series of photographs by Graham Morris. The images, taken with a remote-controlled camera, show Janet mid-air, limbs splayed, her expression a mix of shock and strain. To believers, they’re a rare glimpse of the impossible; to skeptics, a staged leap by a girl known for her athleticism. The levitation claims, debated fiercely, became the haunting’s visual hallmark, a flashpoint for the case’s credibility.

Perhaps most unsettling was the voice phenomenon. By late 1977, Janet began speaking in a deep, rasping growl—far removed from her girlish tone—claiming to be “Bill Wilkins,” a former resident who insisted he’d died in the house. “I went blind, and I had a hemorrhage, and I fell asleep, and I died in the chair in the corner,” the voice croaked, words captured on Maurice Grosse’s tapes. Years later, in 2024, a listener on an LBC radio show identified Wilkins as William Charles Wilkins, a real tenant who had indeed passed away there, a detail that reignited debate about the voice’s origin. Was it a spirit speaking through Janet, or a clever mimicry rooted in something she’d overheard?

These incidents didn’t unfold in isolation. Over 30 individuals—neighbors peering through windows, WPC Carolyn Heeps on her initial visit, journalists like Morris, even strangers drawn by the commotion—claimed to witness pieces of the puzzle. Their accounts, varied yet overlapping, added layers of complexity, suggesting the phenomena weren’t confined to the Hodgsons’ imagination. The activity peaked in late 1977, a frenzy of movement, sound, and spectacle, before tapering off by 1979, its end as mysterious as its start. For 18 months, 284 Green Street thrummed with the unexplained, leaving behind a record that demands scrutiny as much as it resists resolution.

The Evidence – Recordings, Photos, and Testimony

If the Enfield Haunting is a puzzle, its evidence—tapes, photographs, and firsthand accounts—forms the pieces, jagged and uneven, that investigators and skeptics have wrestled with for decades. Maurice Grosse and Guy Lyon Playfair didn’t just observe; they sought to capture the phenomena in tangible form, amassing a trove of material that anchors the case’s mystique and its contention. What they gathered wasn’t abstract—it was raw, audible, visible—but its meaning remains a battleground.

Grosse’s audio recordings stand as the investigation’s backbone. Over months, he filled reel after reel with the house’s soundtrack: sharp knocks ricocheting off walls, furniture crashing in empty rooms, and, most famously, Janet Hodgson’s guttural “Bill Wilkins” voice. The tapes—some broadcast publicly, others pored over by sound experts—preserve a chilling archive. Listeners hear the rasping growl declare, “This is my house,” or recount Wilkins’ death, words that seem to claw their way out of an 11-year-old’s throat. Grosse and Playfair insisted the voice defied Janet’s physical limits—too deep, too sustained—pointing to medical exams that found no strain on her vocal cords. Yet ventriloquist Ray Alan, brought in to assess it, countered that it was a trick, a clever use of false vocal folds any determined child could mimic with practice. The tapes, meant to clarify, instead deepened the divide.

Then there are the photographs, snapped by Graham Morris with a remote-controlled camera rigged to catch Janet in mid-air. The images—grainy, black-and-white—show her suspended above her bed, body arched, nightgown billowing. To Grosse and Playfair, they were proof of levitation, the camera’s impartial timing ruling out human interference. They argued the angles and motion defied a simple jump, a snapshot of the impossible frozen in celluloid. Skeptics, like researcher Melvin Harris, saw something else: a girl bouncing on her mattress, caught at the peak of a leap. Janet’s history as a school sports champion, they noted, gave her the strength and coordination to stage it. The photos, hailed as evidence by some, became ammunition for others, their truth hinging on interpretation.

Complicating matters were the tools themselves. Tape recorders jammed mid-session, their reels grinding to a halt without cause. Cameras misfired or refused to focus, batteries drained in minutes. Grosse and Playfair chalked it up to supernatural interference—an unseen hand meddling with their work—while skeptics dismissed it as mechanical quirks or poor maintenance in a chaotic environment. These malfunctions, frequent yet inconsistent, blurred the line between anomaly and excuse, leaving another question mark in the record.

The human element rounds out the evidence: over 30 eyewitnesses, from WPC Carolyn Heeps to neighbors and journalists, who swore they saw chairs slide, heard knocks, or watched Janet defy gravity. Heeps’ police report carries official weight, while others—like Morris, struck by a Lego brick—bring visceral detail. Investigators leaned on these testimonies, a chorus of voices spanning backgrounds and biases, to bolster the case’s legitimacy. Yet the lack of controlled conditions gnaws at their reliability. No lab, no sealed rooms—just a cluttered house buzzing with media and emotion. Were these accounts glimpses of the unknown, or fragments of a shared delusion?

The evidence of Enfield is a paradox: voluminous yet inconclusive, concrete yet contested. Recordings hum with unearthly sounds, photos freeze moments of apparent impossibility, and witnesses swear to what they saw—yet each piece frays under scrutiny, revealing as much about perception as it does about the phenomena itself.

The Skeptics’ Case – Hoax or Hysteria?

For every knock, levitation, or rasping voice documented at 284 Green Street, a counterargument emerged—sharp, grounded, and unrelenting. Skeptics didn’t just question the Enfield Haunting; they dismantled it, framing the phenomena as a tapestry of trickery, psychology, and circumstance woven by human hands. At the center of their case: Janet and Margaret Hodgson, two girls who, they argued, held the strings to a spectacle that captivated a nation.

Accusations of fakery surfaced early and stuck hard. Investigators caught Janet hiding a tape recorder, its knocks suspiciously timed, and bending spoons—parlor tricks masquerading as paranormal feats. In a rare moment of candor, Janet admitted to faking “2 percent” of the incidents, a confession seized upon by doubters as a crack in the facade. Margaret, too, faced scrutiny, her presence during many events raising questions of collusion. Skeptics pointed to these lapses as proof the sisters orchestrated the chaos—perhaps not all of it, but enough to cast doubt on the rest. A child’s prank, they suggested, snowballed into something larger, fueled by the attention it drew.

Within the Society for Psychical Research, skeptics like Anita Gregory and John Beloff offered a psychological lens. They saw the Hodgson girls not as malevolent schemers but as products of their environment—stressed by a fractured family, a single mother stretched thin, and a home teetering on the edge of instability. The media’s arrival, with its cameras and headlines, only amplified the dynamic, feeding a hunger for significance. Gregory argued the phenomena were exaggerations, small truths stretched into grand tales by girls craving escape or validation. Beloff went further, proposing a feedback loop: the more outsiders believed, the more the sisters performed, each incident a bid to hold the spotlight.

Across the Atlantic, the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal (CSICOP) brought a sharper blade. Stage magician Milbourne Christopher and investigator Joe Nickell dissected the case with a conjurer’s eye. Janet’s “levitation” photos? Gymnastic leaps, they claimed, timed for the camera by an athletic girl who knew how to jump. The “Bill Wilkins” voice? Ventriloquism, a skill any determined child could master, honed in quiet moments and unleashed for effect. They turned the lens on Grosse and Playfair too, accusing the investigators of bias—eager to see the supernatural, they magnified mundane acts into miracles. For CSICOP, Enfield was less a haunting than a masterclass in misdirection, propped up by credulous witnesses.

The skeptics’ case gained traction when viewed through the lens of 1977 Britain. The country staggered under economic strain—strikes, inflation, a gray malaise that left families like the Hodgsons vulnerable. Meanwhile, the public devoured the paranormal, from the TV series The Supernatural to tales of UFOs and ghosts splashed across tabloids. Enfield arrived at a perfect crossroads: a struggling household, a cultural itch for the uncanny, and a media ready to pounce. Was it a deliberate hoax, skeptics asked, or a mass delusion born of desperation and fascination? The girls, knowingly or not, might have tapped into that zeitgeist, their antics—or cries for help—morphing into a phenomenon too big to contain.

The skeptics’ narrative isn’t airtight—unexplained knocks and police testimony linger like stubborn stains—but it’s a compelling thread, weaving the extraordinary back into the ordinary. For them, Enfield isn’t a window to the unknown; it’s a mirror reflecting human nature, fragile and flawed, in a world primed to believe.

The Believers’ Defense – Unexplained Anomalies

Against the skeptics’ tide, Maurice Grosse and Guy Lyon Playfair stood firm, their belief in the Enfield Haunting unshaken by accusations of hoax or hysteria. They didn’t deny the cracks—Janet’s admitted fakery, the bent spoons, the hidden recorder—but they argued these were outliers, a fraction of a larger, stranger whole. Most of what they witnessed, they insisted, defied rational footing. Heavy furniture—wardrobes and tables too bulky for an 11-year-old to budge—slid across rooms with no visible push. Knocks erupted in synchronized bursts, too precise and widespread to trace to a single hand. These weren’t parlor tricks, they contended, but anomalies that strained the limits of explanation. Even Playfair, the more guarded of the pair, wrote in his 1980 book This House Is Haunted that the core phenomena held up, a conviction born from months of sleepless nights and relentless observation.

Their case leaned on external voices too stubborn to ignore. WPC Carolyn Heeps’ police report—a chair sliding four feet under her watch—carried the weight of an official eye, untrained in the paranormal yet certain of what she saw. Neighbors, peering through shared walls or drawn by the noise, described objects airborne and bangs too loud for a child’s fist, their accounts aligning with the Hodgsons’ without rehearsal. Then there’s the “Bill Wilkins” voice—Janet’s guttural claims of a dead man’s life, later tied to William Charles Wilkins by a 2024 radio listener who knew the real tenant’s story. These threads, believers argue, weave a tapestry harder to unravel as mere fabrication, suggesting something—someone?—beyond the girls’ control.

The case also mirrors a blueprint older than Enfield: the poltergeist archetype. Classic traits surface like echoes—chaotic energy swirling around a young person, here Janet, at the cusp of adolescence; bursts of activity that defy physics, then vanish without a bow. Grosse and Playfair saw this pattern as a hallmark, not a coincidence. The disturbances peaked in late 1977, a tempest of movement and sound, before fading by 1979 with no clear trigger—a cessation as abrupt as its start. To believers, this fits the poltergeist mold too well to dismiss as a child’s ruse, hinting at a force that used Janet as its conduit, not its creator.

The human cost bolsters their defense. Janet’s stint at Maudsley psychiatric hospital in 1978 wasn’t a vacation—doctors probed her mind, finding no psychosis, only a girl worn thin by scrutiny and sleeplessness. The family gained no fortune from their ordeal; no book deals or fame cushioned their return to obscurity. Peggy Hodgson lived quietly at Green Street until her death in 2003, Janet avoiding the limelight ever since. Why endure such a toll—public doubt, invasive cameras, emotional strain—for a lie that paid nothing? Believers ask this not as proof, but as a thorn in the skeptics’ narrative, a question that lingers like the knocks once did.

Grosse and Playfair didn’t claim to solve Enfield; they argued it couldn’t be fully solved, not with the tools of doubt alone. The anomalies—validated by outsiders, etched in poltergeist lore, and etched deeper by the family’s scars—stand as their bulwark, a case for the unknown that refuses to crumble under skepticism’s weight.

Aftermath and Legacy

By 1979, the storm at 284 Green Street had quieted. The knocks faded, the furniture settled, and the voice of “Bill Wilkins” fell silent, all without a clear trigger to mark the end. After 18 months of upheaval, the Hodgson family slipped back into a semblance of normalcy, their home no longer a magnet for investigators or headlines. Peggy resumed her life as a single mother, raising her children in the same narrow terrace. Yet Janet, the eye of the storm, later hinted at a lingering unease—minor oddities, she claimed, flickered in the years that followed, faint echoes of a chaos that never fully explained itself. For the Hodgsons, the haunting didn’t conclude with a revelation; it simply stopped, leaving them to pick up the pieces in its wake.

The story, however, refused to stay buried. In 1980, Guy Lyon Playfair published This House Is Haunted, a detailed chronicle that thrust Enfield into the annals of paranormal literature, cementing its status as a benchmark case. Decades later, its reach widened through screens and stages. The 2015 Sky series The Enfield Haunting dramatized the family’s ordeal with a somber lens, while The Conjuring 2 in 2016 spun it into a Hollywood spectacle, amplifying the Warrens’ brief visit into a demonic epic. By 2023, a play featuring Catherine Tate brought Janet’s story back to London’s theaters, each retelling reshaping the narrative—some faithful, others embellished—until Enfield became as much myth as memory. What began as a council house mystery now looms large in cultural consciousness, a tale retold to fit the teller’s vision.

Janet herself, now in her late 50s, has offered rare glimpses into her perspective. In a 2012 interview, she stood by the haunting’s reality—“I know what I went through,” she said—describing events too vivid, too visceral to dismiss as childhood fancy. Yet she’s shunned the spotlight, living quietly with her own family, her words less a defense than a quiet assertion of lived truth. Her mother, Peggy, remained at Green Street until her death in 2003, never profiting from the saga, their modesty a stark contrast to the case’s sprawling legacy. Janet’s reflections don’t settle the debate; they underscore its personal toll, a human thread in a story grown larger than her.

Enfield endures as a litmus test for belief. To some, it’s a credible peek into the unseen—police reports, tapes, and photos forming a dossier too robust to wave away. To others, it’s a cautionary tale of credulity, a house where human quirks and hungry imaginations built a ghost from shadows. The debate churns on, fueled by new voices—like the 2024 radio listener tying “Bill Wilkins” to a real past—or fresh skepticism dissecting old evidence. The house still stands, its current residents reporting nothing amiss, yet its walls hold a history that splits opinion as sharply now as in 1977. Enfield’s legacy isn’t resolution; it’s the tension between what we saw and what we choose to see, a question mark etched in brick and memory.

Conclusion

The Enfield Haunting remains a study in duality, a case where compelling evidence and plausible skepticism collide without resolution. On one side, a mountain of tapes, photographs, and testimonies—from police officers to neighbors—builds a narrative too detailed, too witnessed, to brush aside lightly. On the other, the cracks of fakery, psychological strain, and cultural hunger weave a countertale too coherent to ignore. For every chair that slid, every knock that rang, every guttural word from Janet’s throat, there’s a tug-of-war between the inexplicable and the invented. Nearly five decades on, Enfield refuses to surrender a definitive answer, its truth suspended between what was recorded and what was imagined.

So what do we make of it? Does the chaos at 284 Green Street crack open a window to the unknown—a fleeting glimpse of forces beyond our grasp? Or does it lay bare a human impulse to craft mystery from the mundane, to see ghosts in the shadows of a struggling family and a restless nation? The question isn’t just about what happened, but why it still pulls at us—why we sift through grainy photos and scratchy tapes, chasing a clarity that may never come. Enfield doesn’t demand belief or disbelief; it demands we confront where we draw the line.

Today, the house stands quietly on Green Street, its brick facade unremarkable, its current occupants undisturbed. Yet it remains a silent witness to a story that haunts us still—not just for what might have unfolded within its walls, but for what it reveals about our need to believe, to doubt, to wonder. The knocks have stopped, the cameras have moved on, but Enfield lingers, a riddle etched in a council estate, daring us to keep asking.